Julien Blanchard

All things data | Programming

An example of what we’ll be discussing in this article

Nothing will ever beat wandering on HackerNews before going to bed, reading through random user comments and clicking on links that lead me to an entirely new universe each time. Over the years I've discovered a pretty high number of platforms or tools this way, and I'm really not sure whether I would have even heard of them otherwise or not.

A few months ago, as I was this time reading about the evolution of phrase structure grammar approaches over the past few decades, I stumbled upon a name that immediately rang a bell: Gerald Gazdar. Now if my memory doesn't fail me, I remember first hearing about Gazdar sometime around 2008 or 2009 as I was finishing my studies in Bordeaux.

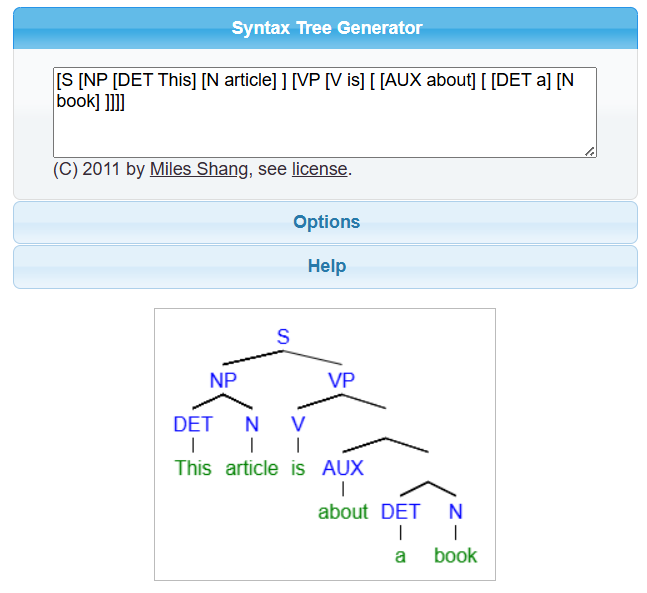

Hearing this name again got me quite curious, and I started researching about what Gazdar had worked on besides for his short-lived and nonetheless ground-breaking theory around generalised phrase / structure grammar. If you're not too familiar with the concept of phrase structure grammar, we're basically talking about one of the most popular ways to represent the construction of any given sentence. Let's consider the following sentence:

This article is about a book

Basing ourselves on the rules of phrase structure grammar, this sentence gets broken down into the following hierarchical representation:

- S stands for sentence and acts as the parent node for the all the following children nodes.

- NP indicates where our noun predicate can be found.

- VP leads to the verb predicate and its children nodes (if any).

- The remaining node are quite self-explanatory I think, and I'm sure you'll have recognised the short form of determinant and auxiliary.

Most linguists will represent the above sentence using a series of nested square brackets:

[S [NP [DET This] [N article] ] [VP [V is] [ [AUX about] [ [DET a] [N book] ]]]]

Despite the original sentence being quite simple, the above notation can arguably look a bit messy. Therefore a common way of representing this type of structure is to use a syntax tree parser. Miles Shang's has been around for a good while now, so we can simply paste the above annotated sentence into his syntax tree generator and see what we obtain.

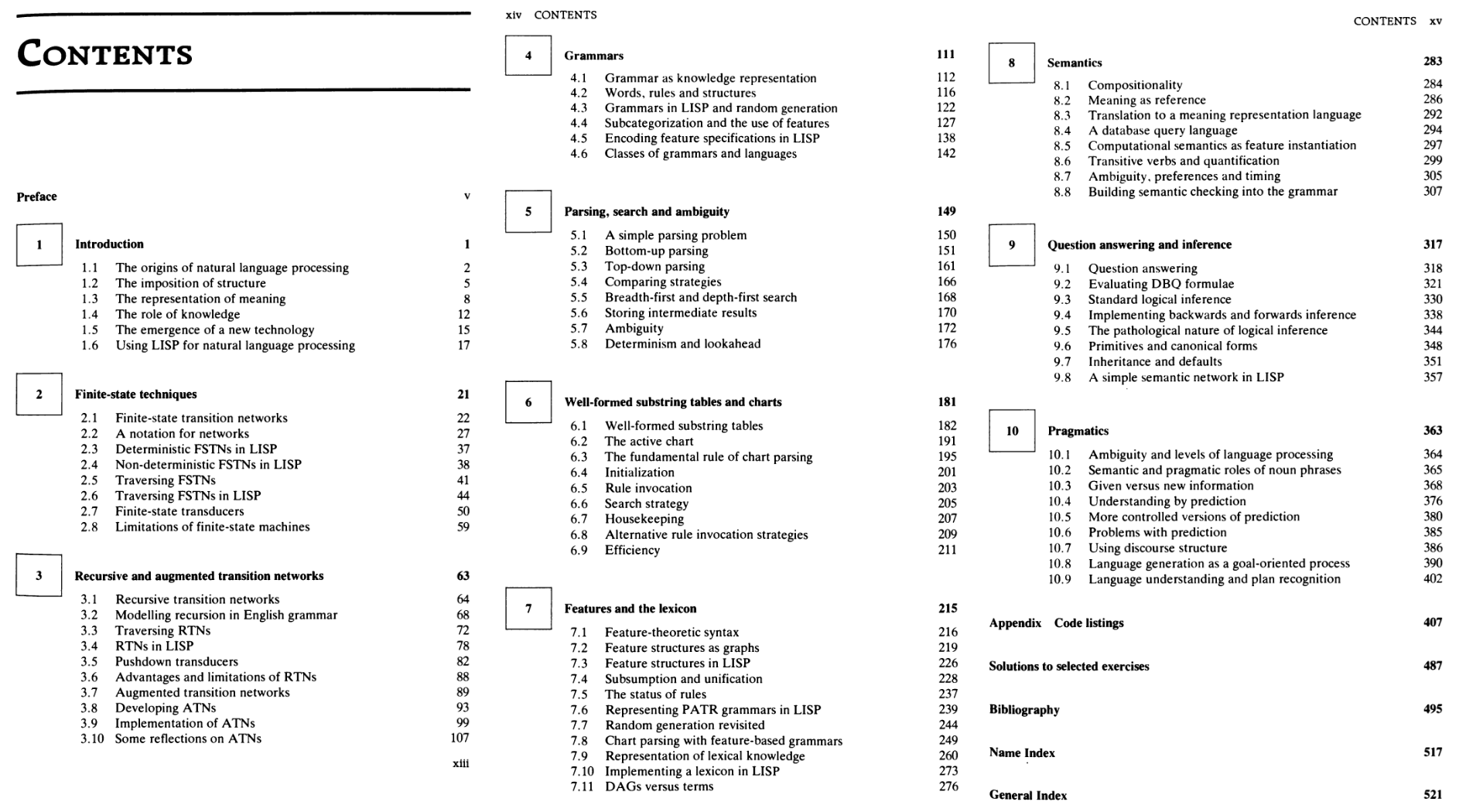

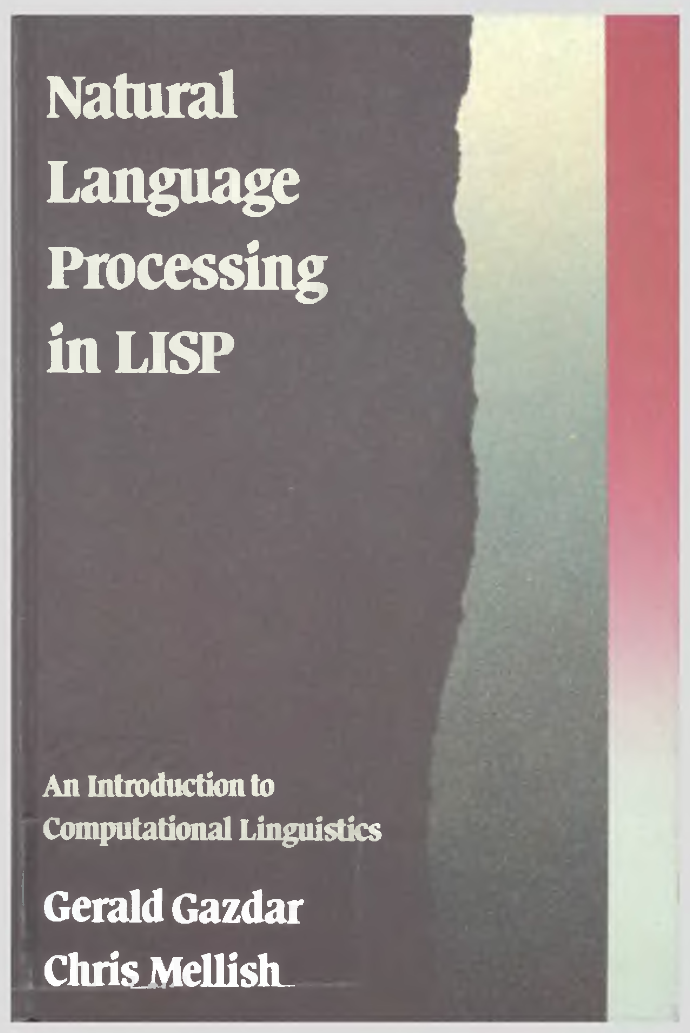

Anyway back to the main topic of this article, I eventually found out that Gazdar had in the early 1980s written two books that became pretty influential in their time:

- Natural Language Processing in PROLOG: An Introduction to Computational Linguistics

- Natural Language Processing in LISP: An Introduction to Computational Linguistics

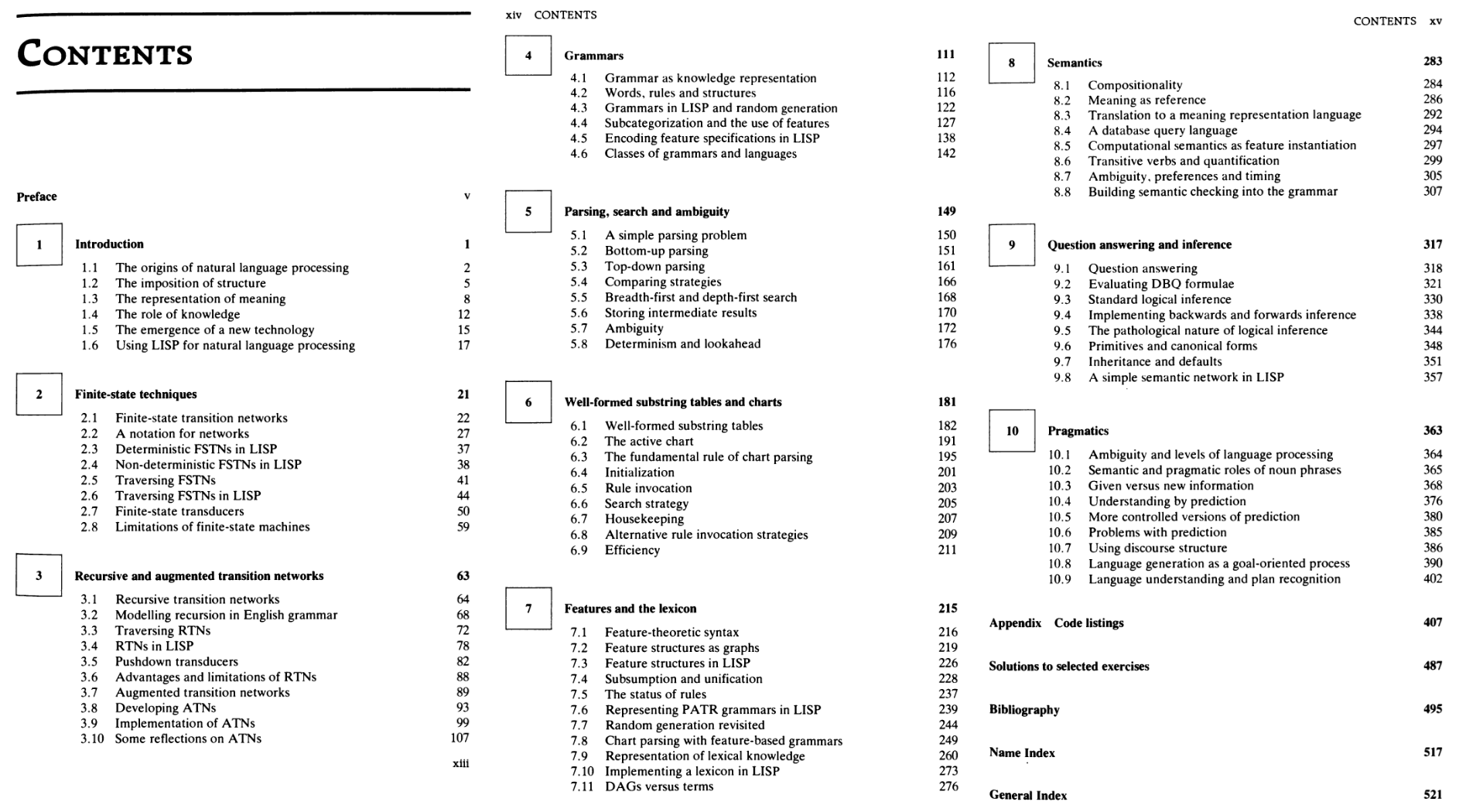

If we refer ourselves to the list of chapters that can be found on the Internet Archive, both books seem to share the exact same content. As can be inferred from their respective title, their main difference is the programming language that is used to implement the various concepts that are covered throughout the 500 or so pages of either version. Now I find that quite interesting, and I don't think that we've seen anything similar in a good while. As in, imagine somebody who would for instance write a book on how to do time-series forecasting in Python, and in parallel also publish the exact same text but this time all the change code snippets to the R language.

As you can imagine, that got me even more curious. Unfortunately a quick search on some online book retailers showed me that there would be no real way to purchase a new physical copy of either the Prolog or Lisp version. Now I did manage to locate some used copies, but immediately decided against going that way as I've had a few bad experiences with second-hand books in the past. You might at this point be wondering what options are left and how I eventually managed to get my hands on that book. Well that's quite simple really: it turns out that Libgen, a platform for downloading scientific papers and books that is most students are very familiar with, offers an ebook version of Natural Language Processing in LISP: An Introduction to Computational Linguistics!.

To my surprise, that digital copy was only available in DJVU format, a file extension that I had never even heard of before. What I found interesting is that the DJVU format was first introduced in 1998, that is to say 9 years after the initial publication of both the Lisp and Prolog books!

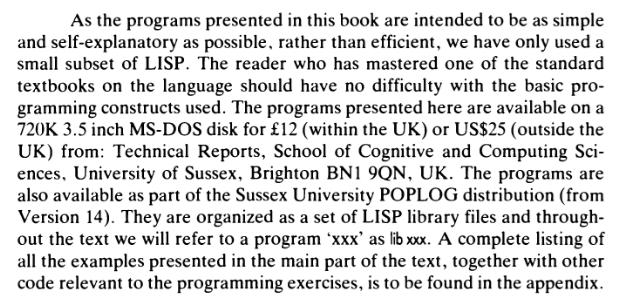

On a funny note, I doubt that a 3.5 inch floppy disk containing the supporting code this book can still be purchased from the University of Sussex:

The 1989 landscape

Before we start dwelving into some of the most interesting chapters the Lisp edition has to offer, it might be worth taking a look at what the computing landscape looked like in the late 1980s.

Let's first consider the most popular techniques that NLP practiotioners have been relying on for a while now, and see whether we could have used some of them or not when the book initially got published:

- Though Inverse document frequency was first coined in 1972, I haven't been able to find any trace of TF-IDF before the early 2000s.

- The same goes for large rule-based sentiment lexicons, with AFINN for instance only being released in 2009.

- I couldn't find much information on lemmatisers or stemmers (like the Porter Stemmer for instance) either.

- Most topic modeling algorithm papers were published much later, such as Latent Dirichlet Allocation which only came up in 2001.

- Etc..

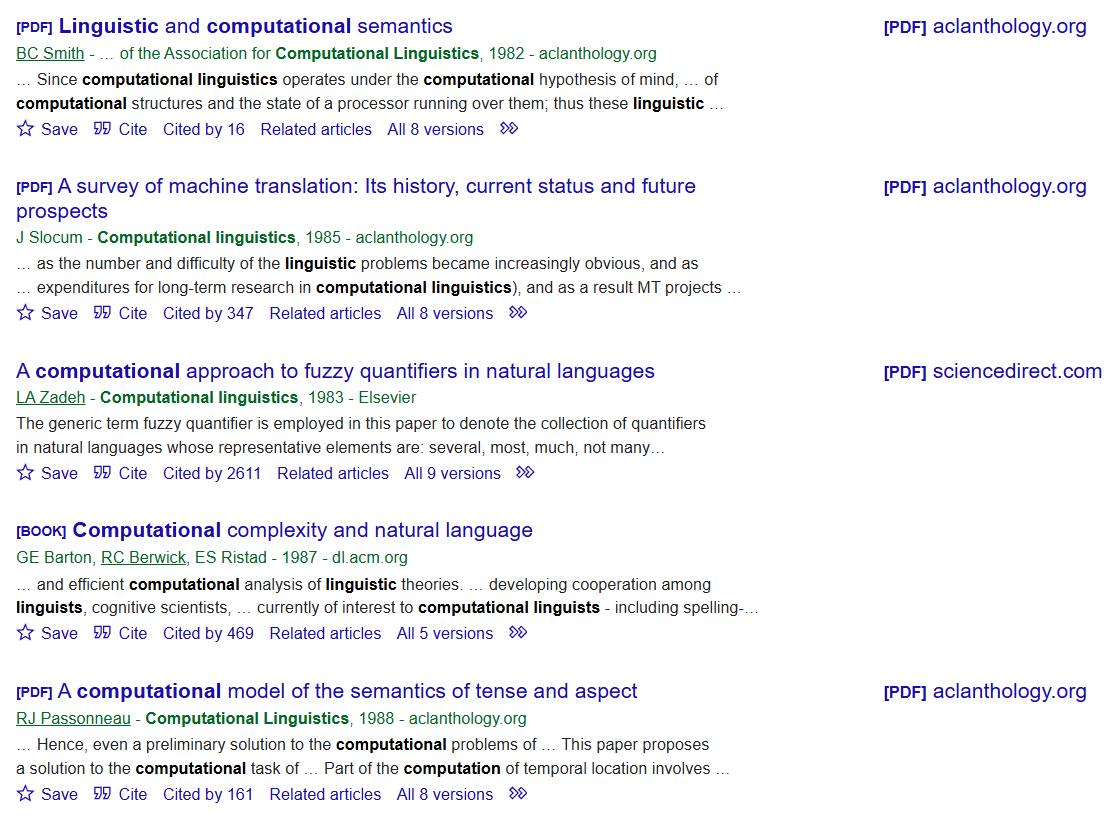

Now don't get me wrong, a quick look at research papers published in the field of computational linguistics before 1989 does return some very interesting results.

If like me you've an interest in programming languages, you might be surprised to find out that Natural Language Processing in LISP: An Introduction to Computational Linguistics was published only one year after the second edition of Kernighan's legendary The C Programming Language, which many consider as one of the if not the most influential programming books ever. But besides C, Lisp and Prolog what would a linguist have used in the late 1980s?

- Forget about popular languages like Python or JavaScript. Both were only developed in the 1990s.

- Perl however came up in 1987, and arguably ent on to play an important role in the development of computational linguistics. Besides Perl 3 was released to the public in 1989, meaning that the Perl community had already started growing.

- Most BASIC family languages, though popular at the time and shipped alongside most home computers, would have been too limited to allow researchers to run anything complex and resource-intensive. That being said, you may consider that some of the numerous adventure games written at that time featured some elements of text processing.

- Another potential candidate would have been Pascal) which on top of being slightly more string-friendly than C had also been widely adopted by universities at that time. That being said I did look for research papers or code repositories showcasing the use of Pascal for language processing but wasn't able to find anything really.

All these languages would have run on the home computers that could be purchased at that time (though I'm not too sure about Perl actually). Growing up in France, I was lucky enough to have access to several of the popular machines, usually through school friends. I have very fond memories of running programns on computers like the Amstrad CPC or the Amiga 500.

That being said, and though we would have gotten several computers at home back in the mid 1980s, I only got acquainted with computational linguistics in the late 2000s while finishing a Master's degree at the university of Bordeaux. As briefly mentioned in another article, our whole class got introduced to Perl through a book named Programming for Linguists:

We got lost along the way

Fair enough, back to the topic at hand then. Let's take a quick look at the table of contents and see if we can spot anything that sounds familiar:

As you've probably noticed, quite a lot of topics are covered throughout the 500 or so pages that the Lisp edition contains. We can narrow these down to the following key concepts:

- Finite-state / Recursive / Augmented transition networks.

- Parsers.

- Rule-based systems (lexicons, etc..).

- NLP tools (question answering, language translation, etc..).

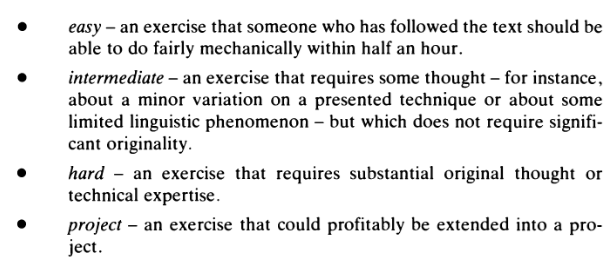

The writing is very clear, and all the chapters contain programming exercises whose difficulty increases each time:

I found the section on parsers to be the most interesting. Though we take this for granted now, one of the early challenges of computational linguistics was building a parser that could represent various grammatical structures. If that doesn't sound complicated enough, add to this the complexity of building parsers across multiple human languages. It reminded me of another great book I read during the pandemic: Brian Kernighan's (again) The Practice of Programming, which had a whole chapter dedicated to building a csv files parser.

Final impressions

Would I recommend Gazdar's Natural Language Processing in LISP: An Introduction to Computational Linguistics in 2025? Absolutely.

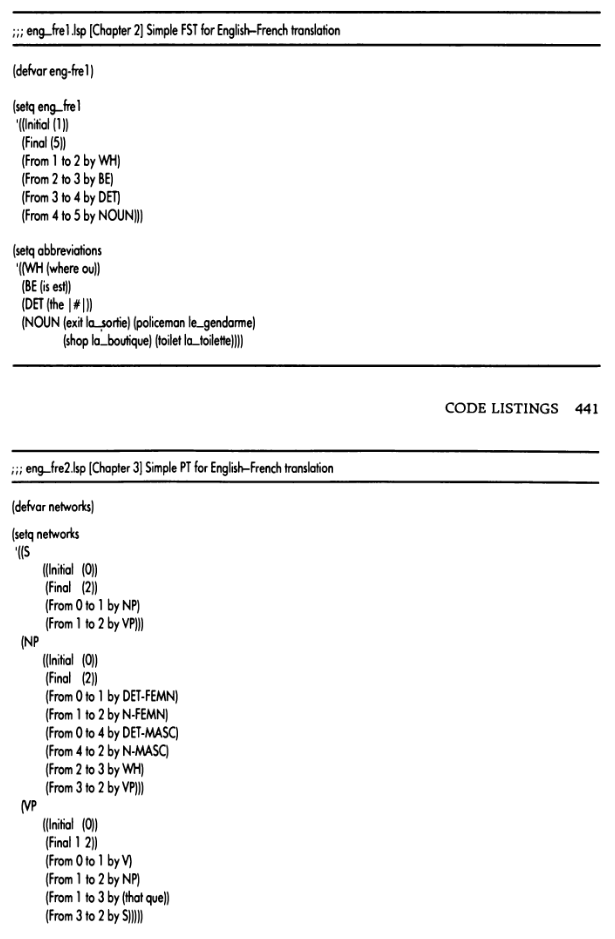

The Lisp edition shows a surprising good balance between linguistics and code. Speaking of which the last chapters contain an introduction to Lisp as well as all the code snippets and exercises that are used throughout the book. As a Frenchman I of course had to pick this specific example:

I'd particularly recommend it to anybody that's ever considered writing their own technical book, or even a thesis. A lot can be learnt from how each chapter is structured. as well as from how all the key concepts are supported by clear and engaging examples.

Definitely a great read.