BERTopic, or How to Combine Transformers and TF-IDF for Topic Modelling

If you follow this blog, you are probably aware of my interest for natural language processing, and more specifically for topic modelling. As a matter of fact, some of the first articles that I wrote back in 2020 were themed around discussing things like TF-IDF and popular text clustering models.

Anyway, if you also happen to share my passion for this niche field, it is quite likely that you have already worked with some or all of the following models:

- LDA: Latent Dirichlet Allocation

- LSA: Latent Semantic Analysis

- NNMF: Non-Negative Matrix Factorization

- GSDMM: Gibbs Sampling Algorithm for Dirichlet Multinomial Mixture

But have you heard of BERTopic? This fairly recent library developped in early 2020, combines a transformers architecture with TF-IDF to allow for the creation of dense clusters. What makes it really interesting in my opinion, is its focus on making each topic interpretable as well as its overall ease of use. BERTopic is able to automatically determine the number of topics within a corpus, and comes bundled with Plotly-based visualisation capacities.

The data

We’ll be using a dataset that contains 700+ recent news articles headlines, that I recently scraped from an online Irish news site named The Journal. The earliest article dates back to August 7th 2022, while the most recent one was published on September 2nd. To retrieve these article titles, I used the popular python library BeautifulSoup, which provides several APIs that can help retrieve the structure of HTML pages and extract their content through XPath-based expressions. It was used, in conjunction with the Request library, to loop through the search results pages and scrape the title of all the articles within each page.

You will find the full code that I wrote to scrape the Journal.ie news site article titles at the bottom of this blog post. But for now, let’s just load the dataset from a .csv file and see what it looks like:

import pandas as pd

def getDataFrame() -> pd.DataFrame:

data = pd.read_csv("journal.csv")

return data

df = getDataFrame()

df.head()

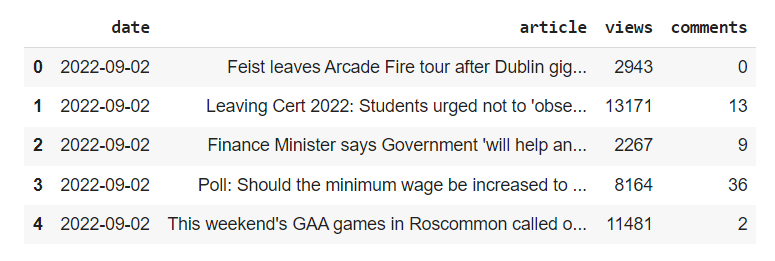

As Google Colab won’t show the full strings that sit within the ["article"] serie, the table below might help explain what the dataset consists of:

| Column | Type | Description |

|---|---|---|

| article | String | The textual content of each article title |

| date | Date | The day and time at which the article was posted |

| comments | Integer | The number of comments left by users under the article |

| views | Integer | The number of times the article was viewed by users |

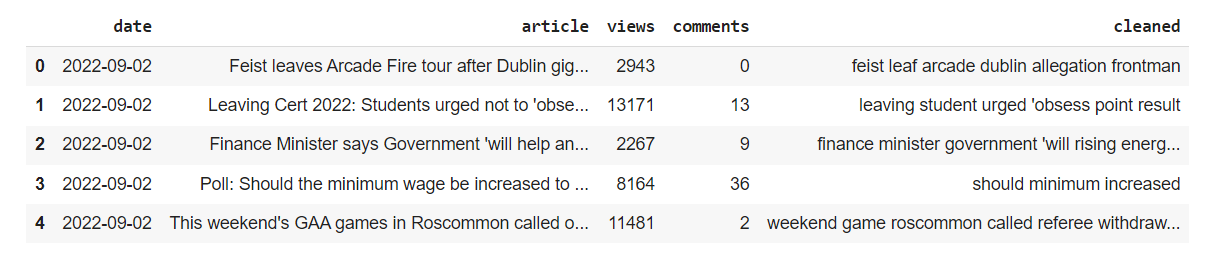

Before we fit our BERTopic model to the textual data we just scraped (or the other way around, if you’re a Wolfram fan), we need to preprocess or “clean” the textual data that lies within the ["article"] serie.

import re

import nltk

import nltk.corpus

from nltk.stem import WordNetLemmatizer

from nltk import word_tokenize

from nltk.corpus import stopwords

def getCleanText(serie: str) -> str:

stop_words=set(nltk.corpus.stopwords.words("english"))

lem = WordNetLemmatizer()

tokens = word_tokenize(str(serie))

tokens = [lem.lemmatize(t.lower()) for t in tokens if t not in stop_words and len(t) > 4]

cleaned = " ".join(tokens)

return cleaned

df["cleaned"] = df["article"].apply(getCleanText)

df.head()

As you can see from the code snippet above, we just removed content that might prevent the model from being able to read and therefore process the information it is fed. Ideally, we really should have used a better list of stopwords than the basic one that we imported from the NLTK library. Most NLP frameworks now provide their own stopwords, sometimes in multiple languages, as filtering these out is especially important for information retrieval and TD-IDF. However, there is no such thing as a universal list of stopwords, and stopwords that are suited for finance will probably be different from stopwords suited for e-commerce.

On a side note, if you are working with a list of tweets, I highly encourage you to read my article on Tweet-Preprocessor.

Tweets will probably contain special characters like hashtags or ampersands, which will have to be removed, using regular expressions. They might also contain typos, abbreviations, and in general words that might not be understood correctly by an English language focused model. For instance, users on Twitter might choose to use common abbreviations such as “btw” for “by the way”, or “imho” for “in my humble opinion” in order to use less characters. Some solutions exist and can be implemented, like looping through each token within a corpus, and comparing the tokens against one of the many human-crafted lists of abbreviations that can be found on GitHub.

There is, however an ongoing debate within the NLP field as to whether or not all punctuation marks should be fully removed during the preprocessing phase or not. For instance, removing the period "." punctuation mark that separates sentences might not affect the meaning of the said sentence. However, removing every single period "." from a dataset would also remove every ellipsis (three consecutive periods), plus the period that accompanies abbreviated strings (ex: “Mr.”, “U.S.A.”, etc..). The same logic applies to question marks, as they allow models to distinguish between questions and statements, which is especially important for coreferencing. In other words, we won’t be removing punctuation marks today.

BERTopic

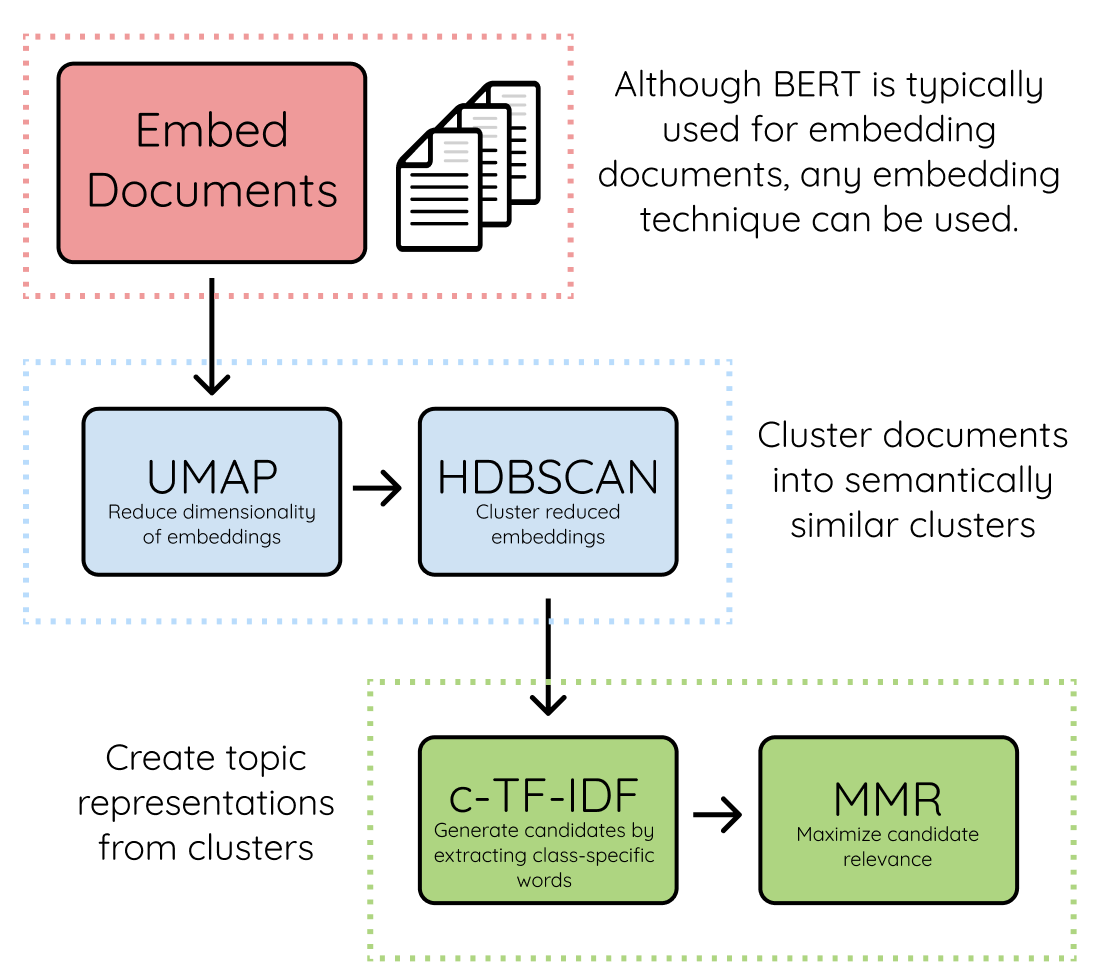

If you want to know more about how BERTopic and it works, the official documentation does a pretty good job at breaking down the steps that this algorithm takes to create topic representations. Its author Maarten Grootendorst provides the following workflow, which explains the three stages that BERTopic relies on:

(source: https://maartengr.github.io/BERTopic/algorithm/algorithm.html)

- TF-IDF

If you’re not familiar with Term frequency-Inverse Document Frequency (or TF-IDF), it is a statistical measure that addresses the issue of some words being attributed a higher importance than others. Being able to determine the importance of a given word in comparison to other words within a whole document is key, and this is why TF-IDF is so frequently used for extracting relevant information from a corpus.

The logic behind TF-IDF is pretty straightforward: the frequency of a word corresponds to the number of times that this word appears in a document. If multiple documents are processed, and a word appears in several of those documents, then its term frequency can be different from one document to another. I wrote a short article about TF-IDF in 2020 if you want to know more. Or simply watch the following video, and actually all the videos from this channel if you some free time:

- Transformers

At a high level, BERTopic takes its inspiration from transformer-based models, which have become increasingly popular over the past few years. Transformers and their pre-trained models are known for representing a more accurate representation of word embeddings.

It uses the sentence-transformers package from BERT to extract various embeddings based on the context of each word. The UMAP package is used to address dimensionality issues, and allows data scientists to manually determine the number of desired clusters and local neighbours (the words that a given word is directly related to). The model then uses a density-based algorithm named HDBSCAN to create the n number of clusters.

What makes BERTopic valuable is its capacity to detect outliers, as well as the fact that it can output what makes the clusters different, through c-TF-IDF, a class based variant of the TF-IDF measure which provides an importance score for each word within a topic.

Practical example

Now that we have preprocessed our data, all we have to do is simply create a list of article titles and assign it to a variable named corpus:

corpus = df["cleaned"].to_list()

Fitting the model onto the data is also pretty straightforward, and if you’ve ever played around with any of the SciKit Learn supported models, the following syntax should be quite familiar to you:

try:

topic_model = BERTopic()

topics, probs = topic_model.fit_transform(corpus)

except Exception as e:

print(e)

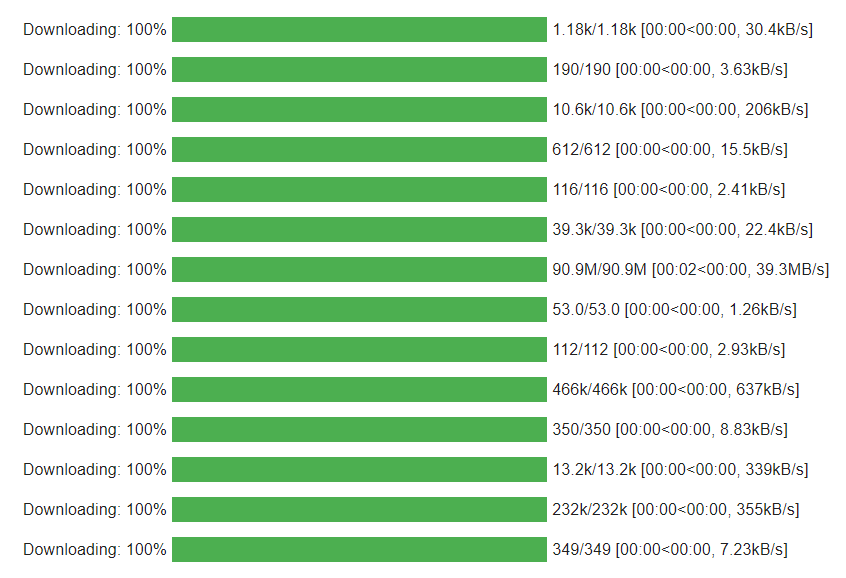

As mentioned earlier, I’m using Google Colab, and what you see in the screenshot below might look slightly different for you depending on the IDE that you are using (if you are using any).

After a bit less than a minute, you should anyway see the green bars reach a 100% completion status, which to us means that we can start exploring the results!

To see how many topics were extracted, and how many tokens are associated to each of these topics, simply type in:

topic_model.get_topic_info()

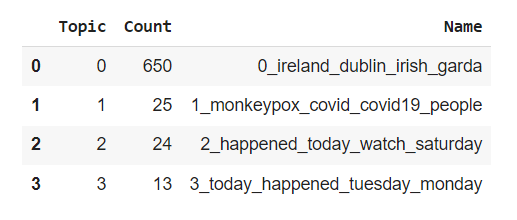

The results are quite interesting. If you head over to the official documentation, you can read the following comment halfway through the Quick start section:

"[Topic] -1 refers to all outliers and should typically be ignored"

In our case, we don’t seem to have any outlier. However, we do have this massive Topic 0 that seems to contain a total of 650 tokens, while our other topics only contain around 20 each. Let’s keep this in mind for when we dive deeper into the actual content for each topic.

.. Which is something that we can easily do by just looping through the get_topic_info() method, and using its index values to output the associated tokens contained within the get_topic() method this time:

def showTopics():

for topics in range(0, (len(topic_model.get_topic_info()))):

print(f"\nTopic: {topics + 1}\n")

for t in topic_model.get_topic(topics):

print("\t", t[0])

showTopics()

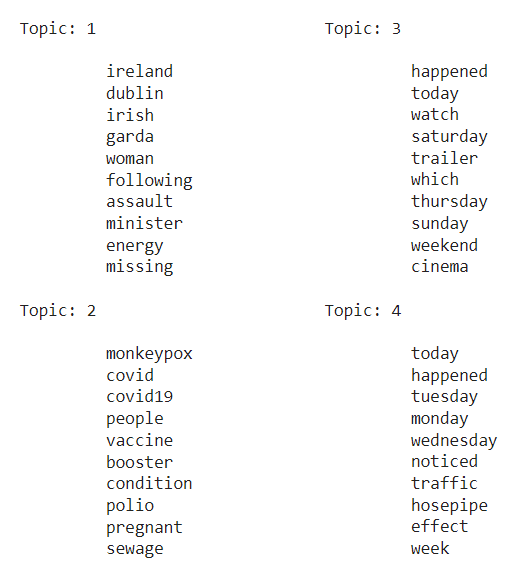

What we can immediately see here, is that we should probably have picked a better list of stopwords! There seems to be a lot of noise within our results, and recurring tokens like week days that don’t really add much value to the overall understanding of each topic.

And yet, though the article titles only cover a 5 week long period of time, and despite our list of stopwords being inadequate for this particular dataset, what we can see in Topic 2 seems pretty accurate. We can indeed see words such as “monkeypox, covid, vaccine, polio, booster that seem to indicate that BERTopic was able to identify a health related cluster of information within our dataset.

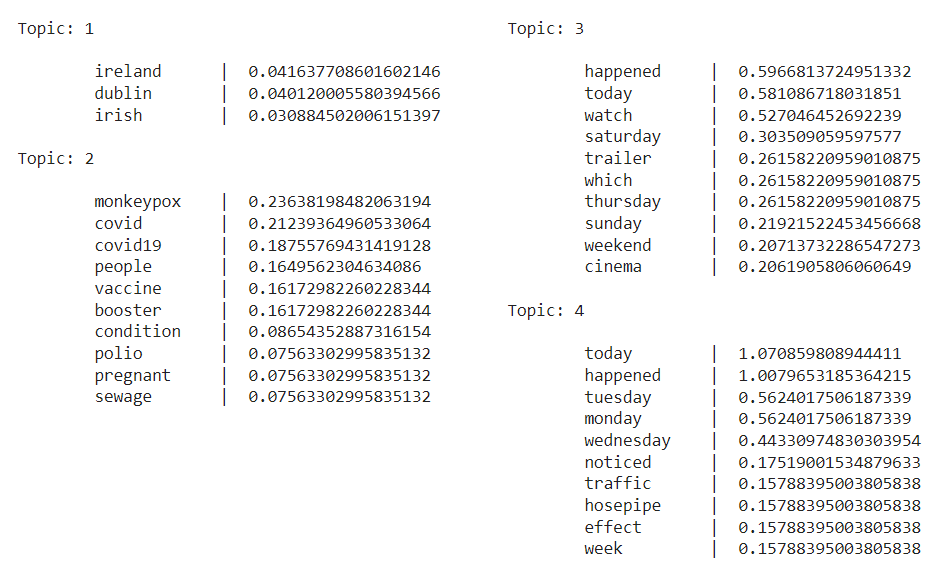

Our next step is to loop through the topics and get the top n words based on their c-TF-IDF scores:

def getTopTopics(min_score):

for topics in range(0, (len(topic_model.get_topic_info()))):

print(f"\nTopic: {topics + 1}\n")

for t in topic_model.get_topic(topics):

if t[1] >= min_score:

print(f"\t{t[0]:<12} | \t{t[1]}")

getTopTopics(0.03)

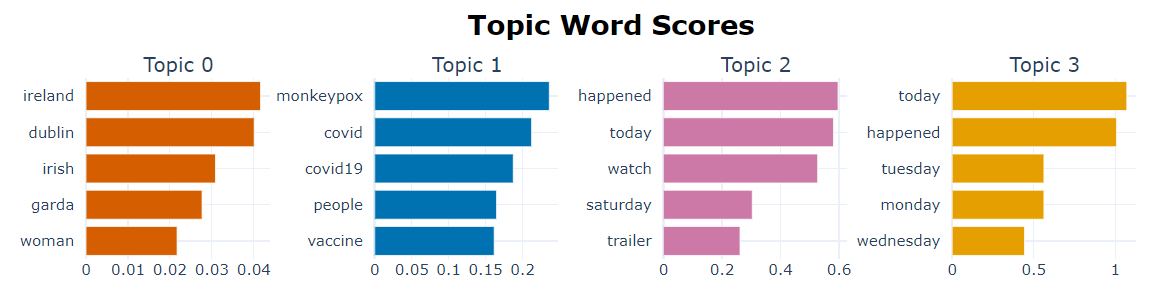

Last but not least, BERTopic also provides a set of Plotly powered visualisations. To be very honest, I find some of them to be not that helpful, but the bar charts that show the top words for each topic based on their c-TF-IDF scores are quite neat (though we could have achieved the same results using any plotting library and the function we wrote just before this one):

topic_model.visualize_barchart()

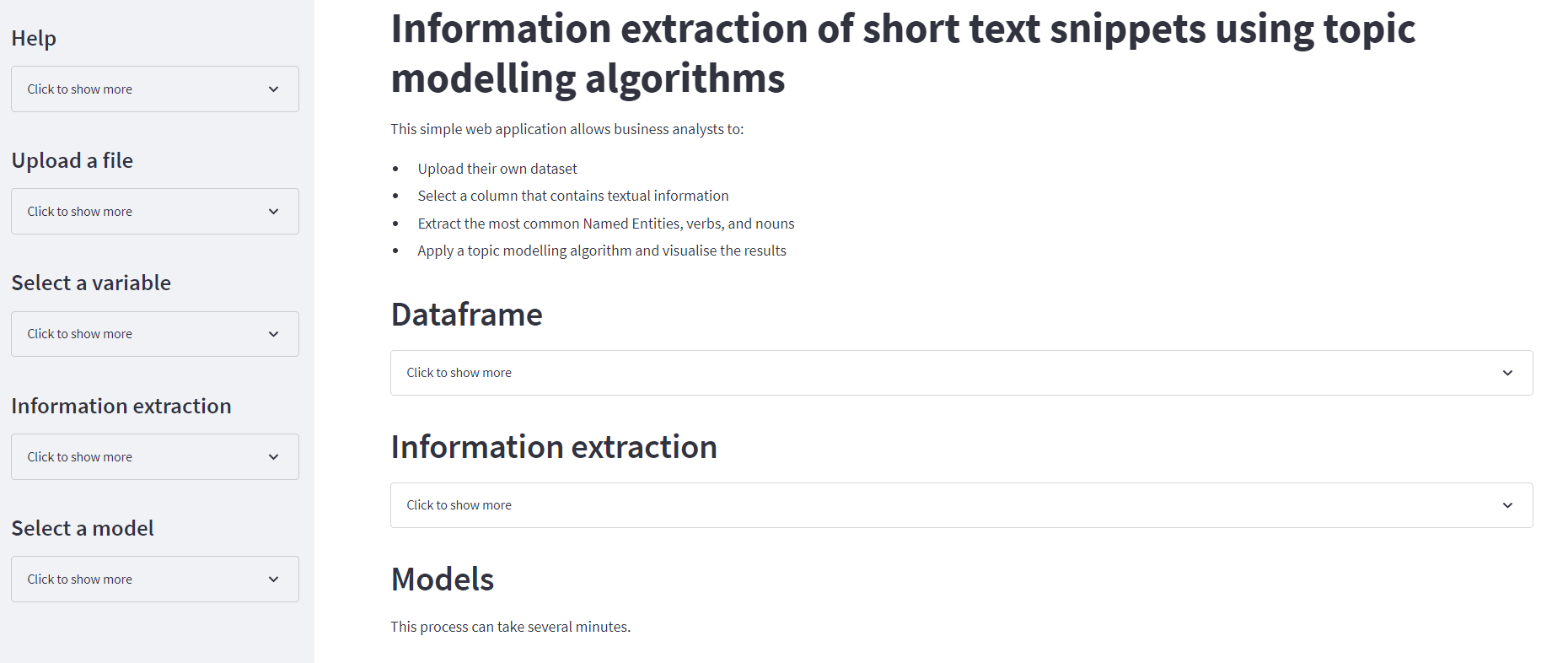

What I find really valuable with BERTopic, is how easy it makes extracting meaningful information from unstructured textual data. We only did some very basic preprocessing, chose an inadequate list of stopwords, and just fed a list of sentences to our model. We didn’t even have to pick the n number of topics that we wanted the model to return, which also allows for embedding this framework into a web application for instance. If you are interested, I actually wrote a topic modelling we application with Streamlit, that you can find here (source code).

Thanks for reading this article, and I hope that you found it useful!

Bonus: scraping the Journal.ie news site

The following code is working as of September 2nd 2002, but since the Journal IE tends to make frequent changes to its UI, I can’t guarantee for it to work in the long run.

import pandas as pd

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

import urllib

import requests

from datetime import date, datetime, timedelta

import random

import re

import time

import numpy as np

# it's clearer if we create a class

class Journal:

# the url embedded within an F-string statement, the number of pages we'll iterate through, and our lists

def __init__(self):

self.Urls = [f"https://www.thejournal.ie/irish/page/{i}/" for i in range(1,20)]

self.Articles = []

self.Published = []

self.Views = []

self.Comments = []

# here we're simply calling the url, and parsing the HTML tags

def getRequest(self,url):

page = requests.get(url)

soup = BeautifulSoup(page.content, "html.parser")

return soup

# that took me an hour, as my initial script was missing the likes and views, but capturing unrelated articles

def getContent(self,url):

soup = self.getRequest(url)

for s in soup.find_all("span", class_="published-at"):

s = s.text.replace("Updated", "")

s = s.replace("Live", "")

self.Published.append(s.strip())

for s in soup.find_all("h4", class_="title"):

self.Articles.append(s.text.strip())

for s in soup.find_all("span", class_="interactions"):

try:

if s.text.strip().split("\n")[2]:

self.Comments.append(s.text.strip().split("\n")[2])

except:

continue

for s in soup.find_all("span", class_="interactions"):

try:

if s.text.strip().split("\n")[0]:

self.Views.append(s.text.strip().split("\n")[0])

except:

continue

# creating dictionaries, where the key is the name of our columns, and the values are our lists

def getDataframe(self):

urls = self.Urls

for u in urls:

self.getContent(u)

limit = len(self.Comments)

df = {"date": self.Published,

"article": self.Articles,

"views": self.Views,

"comments": self.Comments

}

df = pd.DataFrame.from_dict(df, orient="index")

df = df.transpose().dropna()

return df

def getCleanDates(self,serie):

if "update" in serie.lower():

if not re.search("Mon|Tue|Wed|Thu|Fri|Sat|Sun",serie):

return serie.replace("Updated","").strip().split(",")[0]

elif re.search("Mon|Tue|Wed|Thu|Fri|Sat|Sun",serie):

cleanedText = serie.replace("Updated\n","").strip().split(" ")[0]

today = date.today()

for i in range(7):

day = today - timedelta(days=i)

if day.strftime("%A")[:3] == cleanedText:

return day

elif "ago" in serie.lower():

return date.today()

else:

return serie.split(",")[0]

# cleaned dataframe

def getCleanedDF(self):

df = self.getDataframe()

df["date"] = df["date"].apply(self.getCleanDates)

df["date"] = pd.to_datetime(df["date"])

df["date"] = pd.to_datetime(df["date"]).dt.date

df["views"] = df["views"].apply(lambda x: str(x).split(" ")[0].replace(",","")).astype(int)

df["comments"] = df["comments"].apply(lambda x: str(x).strip())

df["comments"] = df["comments"].apply(lambda x: str(x).split(" ")[0] if "Comments" in x else "0").astype(int)

return df

# work your magic, Journal class!

journal = Journal()

df = journal.getCleanedDF()